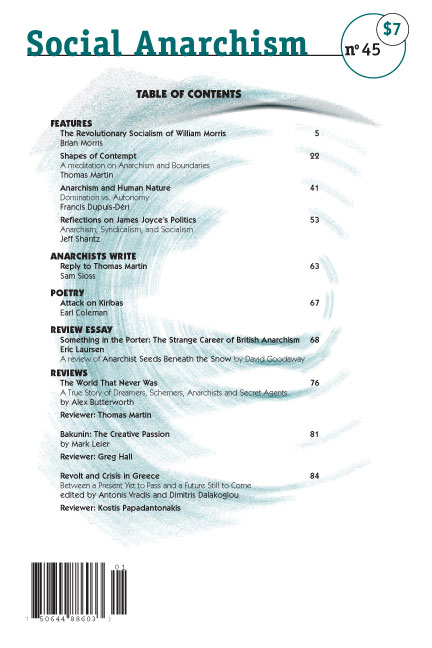

The World That Never Was: A True Story of Dreamers, Schemers, Anarchists and Secret Agents

Alex Butterworth

The World That Never Was: A True Story of Dreamers, Schemers, Anarchists and Secret Agents by Alex Butterworth. New York: Pantheon Books, 2010. xxxiii + 482 pp., illustrations. $30.00 hardbound.

Anarchists have always known that the forces opposing their vision are prodigiously vast and ancient, reaching into every aspect of history and into the deepest crevices of human consciousness. It’s not just Authority in all its manifestations – most people genuinely believe (how could they not, after millennia of brainwashing?) that we need rulers. Hobbes said it best: “without a common power to keep them all in awe,” human life would be “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” It is not surprising that the word ‘anarchist’ conjures up images of terrorism and bombs, conspiracy and assassinations. Butterworth correctly points out (ad nauseam) that the terrorist tactics embraced by some anarchists were counterproductive. Not many of us would argue with that. Assassinations and bombings tend to frighten people and drive them away, not attract them to the cause. And at the same time (witness the Patriot Act) they convince people that the authorities are justified in using those same tactics against the anarchists.

Alex Butterworth is an award-winning writer and broadcaster – not a professional historian, as his publishers claim – who lives and works in Oxford, England. He has written stirringly about the destruction of Pompeii, and contributes to various pop history journals and to BBC documentaries. And there is no denying his talent: The World That Never Was grabs the reader and immerses him in the shadowy world of nineteenth-century radicals, double agents, secret police, and utopian fantasizers. The narrative is gripping; but if you’re looking for analysis, look elsewhere.

Butterworth suggests that all the exertions of the radicals – from the Paris Commune to the assassination of Alexander II – were little more than ripples on the surface of a calm and complacent capitalist-authoritarian ocean. Sadly, he’s probably right. As this reviewer has learned over many years of teaching European history, few if any college students have ever heard of Kropotkin or Reclus, and even when enlightened, cannot comprehend what these brilliant minds were trying to say.

From cover to cover, the work is at once fascinating and hard to follow. Butterworth jumps from one topic to another like a meth-addicted raver. In chapter five, “To the People,” we start with the Chaikovsky Circle, and then suddenly leapfrog to Auguste Comte and Charles Darwin, then to Kropotkin’s relationship with Chaikovsky, then to Dostoevsky, then back to Kropotkin in his cell at the Peter and Paul Fortress. The reader is challenged throughout the book with the need to hold in mind a dozen different narrative threads at once. In the first chapter, we are treated to an irrelevant dissertation on the role of a cutting-edge technology – balloons – in the history of the Paris Commune. Seurat’s paintings are explored in juxtaposition with Louise Michel’s opinion on prostitutes’ argot, and even Jack the Ripper makes an appearance. Admittedly, this everything-but-the-kitchen-sink approach does help the reader engage in the atmosphere of the times.

For the serious historian, this work crosses the forbidden boundary into the realm of fiction. To his credit, Butterworth admits to having invented some incidents and conversations to bridge gaps in the documented record – not many; but one has to wonder how many more he does not disclose. The “Notes on Sources” reveal such thorough research that such fabrications seem unnecessary. Some passages are based on quite reasonable speculation, but others would mean denial of tenure at most universities: for example, he states as a fact that the nefarious Protocols of the Elders of Zion was a project of the Russian secret police, the Okhrana, under its diabolical chief Pyotr Rachkovsky. He may be right, but the question is far from settled. Kropotkin’s evolutionary ideas as expressed in Mutual Aid (a work, by the way, never mentioned by name in this book) were “the proof of mankind’s inherent perfectibility” (318) – a telos that Kropotkin, of course, never laid claim to; but the assertion is necessary to Butterworth’s thesis.

Lest this review sound like a blanket condemnation of Butterworth’s effort, this has to be said: today’s anarchists, at least some of us, have a lamentable habit of idolizing the great theorists of the past. Kropotkin, far ahead of his time, saw the necessary link between evolution, ecology and anarchism, and inspired the work of Murray Bookchin. Bakunin was the fearless advocate of revolutionary violence: “the passion for destruction is a creative passion.” And we have our martyrs: Sacco and Vanzetti, the Haymarket eight. All true, but Butterworth reminds us that Kropotkin never entirely sloughed off his aristocratic heritage, and that Bakunin was foolishly “enchanted” by Nechaev – and was an anti-Semite to boot. Too often, anarchists fall into the trap of hero worship. We tend to forget that the great theorists and activists were human beings, enmeshed (as we all are) in the web of their own times. They made mistakes, they conspired against each other, they were jealous and vindictive; at times they even betrayed their own convictions. Their failings subtract from their intellectual achievements only when we overlook them.

From one perspective, The World That Never Was can be seen as a lengthy commentary on ‘lifetstyle anarchism.’ Many of the radicals depicted here held jobs, paid taxes, had bank accounts, sometimes even owned property or businesses. All of them took part, to some extent, in the capitalist system – even those in prison. Butterworth implies, but never quite says, that this participation compromised their radicalism, made them hypocrites. I suspect that Murray Bookchin, leading polemicist of lifestyle anarchism, would have said that Butterworth goes too far. Anarchism has failed to resolve the tension between individualism and collectivism, as Bookchin said. In the period covered by this book, it was the collectivists who most influenced the working class and wrote the great anarchist classics, while the individualists threw the bombs and lived what Bookchin (somewhat unfairly) calls the “bohemian lifestyle.” Butterworth, however, never clearly distinguishes between these two poles. Given his deep research and attention to detail, one cannot believe that he simply overlooks it. Rather, he deliberately conflates individualism and collectivism (taking advantage of the fact that at times, nearly all anarchists have a foot in both camps) in order to dismiss all anarchists as ‘lifestyle.’ Acknowledging the sincerity of such intellectual giants as Bakunin and Kropotkin, and admitting that their lives were distorted by the ineluctable pressure of state authority, he nevertheless leaves us with the impression that all these men and women were sophistic frauds.

Butterworth’s sarcastic and snide descriptions of the anarchists and other radicals betrays his reactionary agenda. While he rightly condemns the tactics of the secret police, Butterworth tacitly approves their goals by likening them to today’s anti-terrorist warriors. A clever choice of adjectives and incidents stands in for rigorous analysis. While he never openly takes sides – he castigates the capitalists and police too – it is clear that he has no sympathy with anarchism or any other left of center ideology. A few examples will suffice. Bakunin is a “corrupt husk” (111); Johann Most had “an aptitude for melodrama” (130); Emma Goldman’s name is mentioned only in connection with the Berkman-Most-Goldman love triangle and with her brief encounter with McKinley’s assassin Czolgosz. Radicals and their police pursuers dwelt alike in “a diabolical realm of shadows . . . a world in which the boundaries of reality and invention were blurred.” (4) Butterworth himself seems to dwell there, too. His account of the Haymarket incident is fair and balanced, though he gives only one sentence to the possibility that the bombing was a police plot. Disproportionate attention is given to anarchist-inspired acts of violence, “the last resort of the hopeless, the damaged and the dispossessed” (361) – well, okay, assassinations are more alluring than philosophical treatises.

The governments of Russia, Germany and France – to a lesser extent, of England and America, and even Switzerland – employed violence, lies, blackmail, intimidation, double-dealing, and flimflammery of all varieties against the radicals. This is no surprise: government is after all founded on violence and the threat of violence. But we don’t always realize that state oppression forced anarchists to adopt the same tactics. In order to stay out of prison, or even just survive, anarchists had perforce to organize, conspire, and abandon their own principles. Moreover, radical activity sometimes had unintended and nasty consequences, such as aggravating the already noxious anti-Semitism of the era.

Perhaps the best part of the book is near the end, as Butterworth describes the radicals’ reactions to the outbreak of World War I and the runup to the Russian Revolution. As he rightly points out, the anarchists were running out of steam, the old Communards were aging or dead, and the Marxists were in the ascendant. Many radicals abandoned their internationalist principles to take sides in the war; even Kropotkin did so, explaining that the struggle was so vast and Manichaean that it superseded all past considerations. He was right, of course; though the new world that emerged from the bloody trenches was not what he had in mind. Anarchism had to be reforged, but this book makes no mention of that challenge, merely recording at the end of the last chapter that Malatesta “was left untouched to grow old in voiceless frustration, finally dying in 1932.” (410) There is, however, a “Coda,” in which Butterworth redeems himself somewhat. Though he calls naïvety anarchism’s “fatal flaw,” he concedes that its failures have usually been the result of disproportionate state persecution, not of its philosophy.

Some cogent questions are raised: has anarchism been self-defeating, in the sense that it provides the bogeyman that authoritarian institutions need to justify their existence? Does traditional anarchism (forgive the oxymoron) exhibit many of the marks of Judaeo-Christian-Islamic religion: martyrs, blind faith, fanaticism, the cosmic battle of good against evil? And is it even possible to be a ‘real’ anarchist while enmeshed in the matrix of capitalism and authoritarianism?

Books like this are a valuable purgative for us anarchists, whether ‘lifetyle’ or ‘punk’ or ‘purist.’ The baby must not be thrown out with the bathwater, but the bathwater must indeed be thrown out. Anarchism went through its first great crisis during World War I, redefining itself just as all ideologies had to do. It is going through its second paradigm shift now, as it struggles to deal with new scientific findings about what it means to be human. And Butterworth’s anarchists are as human as one could wish for.

Thomas Martin teaches American history and subverts the dominant paradigm at Sinclair Community College in Dayton, Ohio.